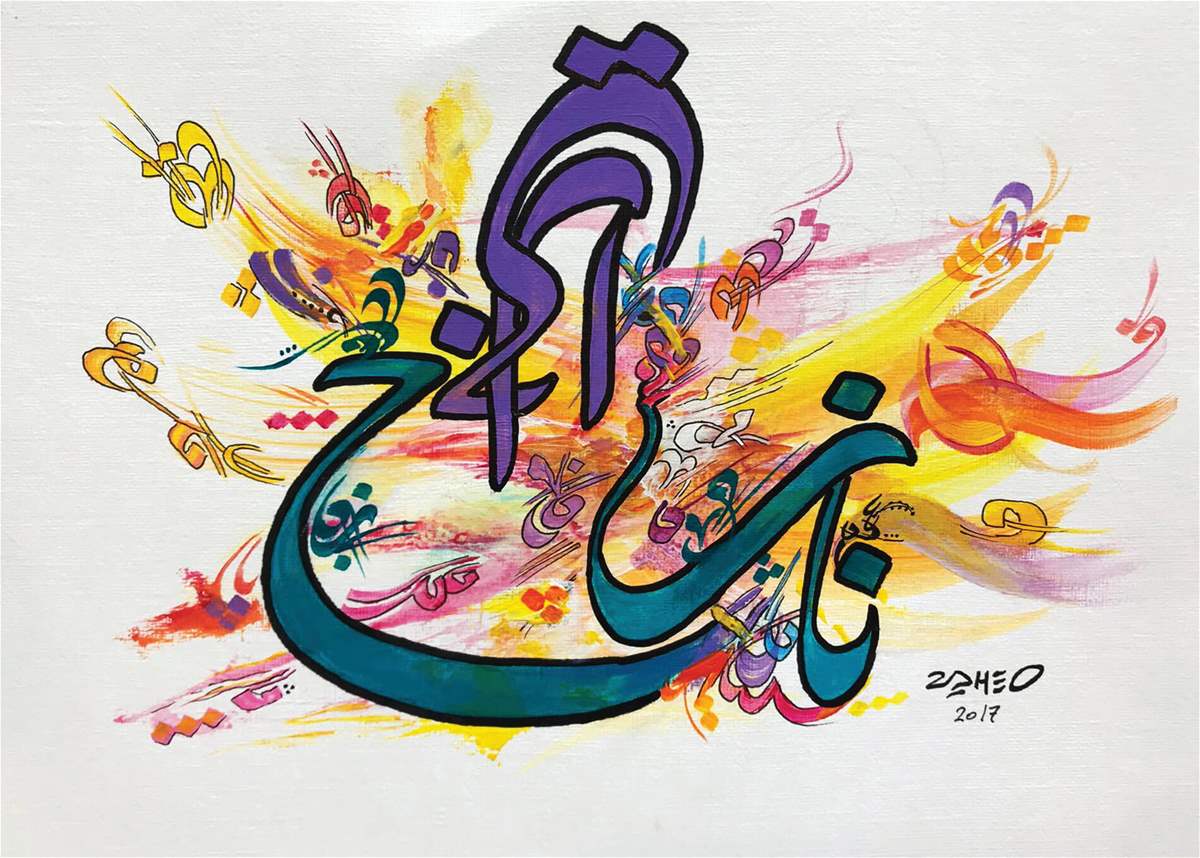

The idea shows the difference between nuzuh or displacement in Arabic and luzhu’ or asylum-seeking in Arabic through the way the two words are written. Nuzuh was a single block with the letter h distancing itself away from it but at the same time hanging at the end of it, indicating displacement and seizing the opportunity to return. Small letters and diacritics squeezing together over- lapped, as if emitted from within it, indicating a longing to return and forming a single block again, i.e. "the return of the letter h to the letters n, u and z".

As for luzhu’, the letters appear closely knit, twisting on themselves, indicating assembly in a small space twisting on itself. The two words appear homologous because they hold a meaning and its antonym.

The discussion broadly starts with the obvious debate on the identification of these individuals. The latter has led to a pathetic epic journey of wording and expectations. Since the beginning of the influx of the Syrians into Lebanon, as a result of the armed conflict, the Government of Lebanon dissociated itself from the crisis. More dangerously, the Lebanese government shifted the responsibility onto the myriad of international organizations working in Lebanon and on donor countries alike. This was accompanied by a series of internal communication and political messaging at the national level.

The Lebanese government has since 2012 utilized the word "displaced Syrians" in order to refer to Syrian refugees in Lebanon. The position is strongly built on an assumption that referring to refugees as displaced would relieve the State of Lebanon of its responsibilities. This approach raises two main concerns. The first is the shifting of the discussion to a linguistic exercise of brainstorming a semantic field of movement and mobility. The early years of the crisis focused largely on ensuring that communication with regard to the humanitarian crisis excluded the word refugees. The second concern, which is more dangerous in nature, lies in motivations and intentions. By adopting such terminologies, the Government of Lebanon aims at escaping from obligations and responsibilities falling on any duty bearer within the human rights framework.

The question remains of whether people have fewer rights if they are called displaced. Is the Lebanese society more resilient by perceiving refugees with different wording? Although not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, Lebanon nevertheless has obligations towards Syrian refugees and cannot allow them to fall into a legal black hole, even in the context of mass influx. A series of existing international norms are indeed applicable regarding the non-refoulement of persons fleeing a conflict, but also their protection and reception conditions in the host country. Such norms should be interpreted in a mutually reinforcing manner for the protection of refugees and asylum seekers. It is paramount to stress that the situation of mass influx cannot be invoked by Lebanon to violate the principle of non-refoulement and core international human rights obligations.

On the other hand, several terminologies, despite their correctness legally, could also fuel further tension among host and refugee communities. An understanding that many Syrian nationals are "irregular" in Lebanon or a number of Syrians are detained for "illegal entry" or "illegal stay" spreads a perception of insecurity among communities. Lebanon has a valid interest in ensuring the stability and security of the country, however the category-based restriction of movement, including arrests and detentions, and the persistent mistreatment and stigmatization of refugees should be addressed within the rights-based context. The rigid policies implemented on Syrian nationals in Lebanon, in addition to curfews, raids, arrests, and violations to the presumption of innocence, have generated a strong perception among Lebanese coining refugees as a security threat. The latter perception generates further segregation of communities and discrimination leading to weaker social cohesion and further challenges to stabilization interventions.

While the media and social dynamics play a significant role in framing attitudes by placing blame or targeting specific communities, the authorities, in conjunction with other relevant organizations, including civil society and humanitarian actors, should examine ways in which social cohesion can be built and maintained. Changing perceptions and attitudes towards refugees so that they are viewed within the context of their unembellished reality, rather than perceived as an inherent socio-economic and security threat, is fundamental to addressing misperceptions, which have fostered jealousy and resentment in Lebanese public opinion.

In conclusion, the constant shifting of responsibility and creation of an environment of dependence and lack of protection could be counter-productive for the concerns of the Lebanese government and the interest of its society. It is of ultimate need that debates currently taking place with regard to a comprehensive policy document for the Lebanese government address these challenges. It is important that even when discussing solutions to the crisis, Lebanon’s decision makers focus on the return to Syria, blindsiding protection and rights-based elements for Syrian refugees, who in any case, will have to spend several years in Lebanon.