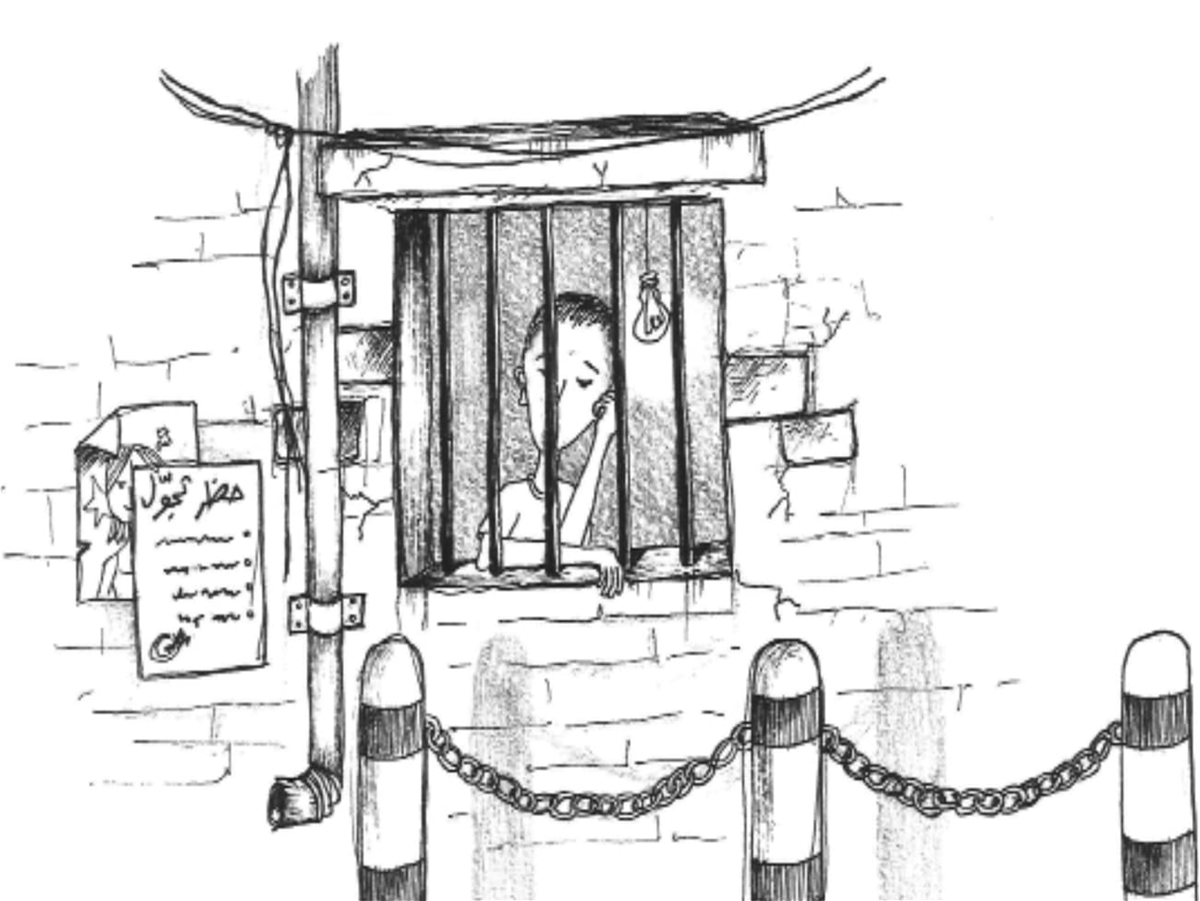

While the concept itself is rather ancient, it started being used in the early 1900s as a crime control strategy concerning juveniles.(1) Even though these measures can be very efficient from the criminological point of view, they raise serious concerns with regard to fundamental rights. Freedom of movement and assembly clash with public order, more specifically public security and safety. In Lebanon, management of circulation and protection of public safety and security are under the jurisdiction of local authorities and more specifically municipalities, under section 74 of the Municipal Act number 118 dated the 30th of June 1977. In a context of Syrian crisis, armed conflict in Syria that shares large borders with Lebanon and terrorist attacks perpetrators on Lebanese territory, security and public order have become a priority for local authorities and State law enforcement offices, especially after summer 2014. Municipal prerogatives with regard to the management of the consequences of the Syrian crisis within their territorial jurisdiction have been enlarged by the Minister of Interior. Curfews have been installed by municipalities throughout Lebanon as a preventive method in a more systematic way than usual, curfews being an exceptional measure, usually undertaken as a response to a security threat, potential or real. With the increase of refugee population in Lebanon, sometimes exceeding the number of Lebanese citizens in certain areas, especially villages, these measures are imposed by municipalities subsequent to attempts to persons or properties, verbal or physical harassments, according to a municipality in South Lebanon for example. In other words as a response to disturbance to public order and as a prevention to further disturbances, which is why they are recurrent in border areas more likely to be influenced by the armed conflict in Syria and subject to unofficial cross border activities, such in Bekaa. Therefore, within the scope of their territorial jurisdiction, municipalities use curfews as a mean to maintain public peace and tranquility and/or prohibit attempts to it.

They are also used as a mean to control demography. More interestingly, some municipalities clearly stated they had to take this kind of measures in order to prevent self-protection measures by Lebanese citizens and further tensions between Syrian and host communities. Curfews are justified by local authorities as enabling them to protect local population and maintain public order. In order to analyze the situation of curfews imposed to Syrian refugees, one should examine the conditions of its installment as per Lebanese laws. Local practices show that curfews are usually imposed at night starting 7:00, 8:00 or 9:00 PM till the early morning, usually end around 6:00 AM. In many areas they contain gender limitations, targeting men only. Surprisingly, in some areas, women movement and gatherings were allowed at night while male gatherings were strictly prohibited even during daytime, since women are not perceived as a security threat or having a tendency to participate to illegal activities. Concerning sanctions, it has been noticed that municipalities apply a gradual response mechanism. Violators of curfews are often warned when caught for the first time and arrested if the act is repeated. Also, in many areas, exceptions allow breach of curfew such as emergency medical situations. This being said, the use of such prerogatives by authorities have to be examined with respect to fundamental rights and liberties. In fact, implementation of curfews raises several human rights related questions: attempt to public liberties, more specially freedom of movement and arbitrary arrest, since violators of curfews may be arrested by local authorities. Articles 8, 9 and 13 of the Lebanese Constitution protect freedom of movement, conscious and assembly. However, the exercise of these freedoms is limited by Law and public order. Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognizes a person’s right to freedom of movement and choice of residency within the territory of a State. In this perspective, installing curfews reflects a practice that attempts to individual liberties guaranteed by both national and international instruments. Therefore, deprivation of liberty is the exception and has to be subjected to strict control. Lebanese case law supports this interpretation of constitutional rights(2) that need to be guaranteed. Judicial control is exercised to control the consequences of municipal action since the judicial judge is the «guardian of individual liberties». Any unlawful attempt to such right may be subjected to judicial review under cumulative conditions: material action taken by the administration, attempt to the right to property or individual liberties and extensive violation that taints the action of administration. In this regard, questions can be raised concerning the duration of arrest or detention, the necessity of an administrative control or the possibility of a judicial control in practice, the necessity of clear instructions to limit the discretion of local authorities to the strict requirements of specific security situations concerning their territory. In case of abuse, the administration must be held accountable. As preventive measures, curfews are proportional to the perception of threat in a certain area. This explains the difference of application noticed between rural areas and Beirut for example. Small villages being geographically easier to control, most curfews are imposed in rural areas where the effective and strict implementation is more possible than in the capital city. It has also been noticed that curfews are less likely to be observed in districts like Ashrafieh or Hamra and law enforcement officers are more likely to be permissive and less inquisitive than in rural areas. This fact creates a discriminatory situation within refugee population based on their social and financial status. Direct interaction with Syrian refugees in the Bekaa valley allowed to have an honest feedback from the latter regarding curfews. While all interviewed persons agreed on the fact that these measures were restrictive, especially in case of emergency at night or in terms of having a social life and paying visits to friends and relatives, the tradition «Sahar», most of them understood the security motivations. However, they wished authorities could use other methods to ensure public safety without penalizing an entire community. Refugees also expressed the feeling of being discriminated against since curfews were only imposed to Syrians and no other nationalities. Discrimination appears also in the abovementioned articles of the Constitution protective to freedoms since they are listed under «Chapter 2 the rights and duties of the citizen». In other words, its scope does not clearly include non-citizens, refugees or not. The latter will have to seek the protection of international instruments regarding violations of these rights.

Conclusion

Distinction between educated and uneducated Syrians by the Lebanese administration. While this has been reported as a positive treatment from Lebanese authorities towards Syrian nationals of a certain social status, thus distinguishing and acknowledging their social and educational background, one may wonder if persons not belonging to a certain social category should be treated with the same regards.

(1) Crime and Punishment: A History of the Criminal Justice System, Second Edition, Mitchel P. Roth, page 31.

(2) Judge for expedited matters of Beirut held a decision on the 20th of June 2014, (Adel, Part Two, 2015, page 1049).